We are among those individuals who vastly prefer Gallup to Santa Fe. At this point, some of you will wish to roll your eyes and stop listening. I remember Santa Fe from the early 1960s. Yes, I was a young girl then, but Santa Fe truly had the look and feeling of a small European city to someone from upstate New York. In the intervening decades, Santa Fe’s charm has been whittled away by the demands of tourism and urban planning. With Gallup, what you see is what you get.

Gallup is a railroad town and its tracks define the whole sinuous curve of its old Route 66 highway. The rest of the town is sprawled over its rolling hills and graceful valleys. Because it serves as a reservation border town, Gallup has also attracted the least admirable publicity. Back east, I know people who shiver at the mention it, speaking in shocked tones of horrible car accidents, drunks staggering along streets, and an unnamed discomfort. Friends of ours from Arizona shake their heads at our affection for it, claiming they’d only stop in Gallup for a gas station.

When we visit Gallup, we get a sense of what the West is really all about. We don’t need a movie set, a romantic view of mesas and buttes, or a string of trendy eateries to feel that here is a place where real people live, work, visit, shop, and that life in a railroad town is about staying put while all about one is motion. The people are nice, too, friendly in a way that is far more realistic than people one encounters in a popular tourist destination.

A train arrives in Gallup — one of many arrivals every day.

A train arrives in Gallup — one of many arrivals every day.

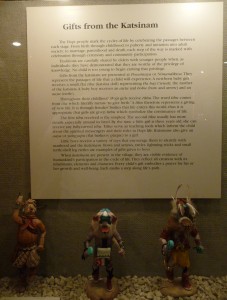

While staying at a Scottsdale resort in early August, I discovered it had a Native American Cultural Discovery exhibit. I’m always interested in finding out what those in the hotel business consider important for visitors to learn about Indians. The decent-sized room had several cases that focused on kachinas, or katsinum as they’re called by the Hopi. These Pueblo Indians are not the only ones to have developed a large hegemony of sacred beings, but their carved cottonwood dolls are one of the greatest categories of collectibles in the American Southwest.

Hopi katsinem are also one of the most recognizable “brands” of types of Indian arts. They vary from elaborate sculptures worth thousands of dollars to modest handmade figures sold at souvenir prices. I find the katsina figure to be a real paradox: on one hand, it represents a genuine sacred spirit possessed of powers important to the Hopis and a means of teaching their children, on the other hand it conveys an immediate exoticism and “otherness” that specific souvenirs conjure up just by their existence.

Gifts from the Katsinem

Gifts from the Katsinem

Katsina of Angwusnasomtaqa by Brian Honyouti

Katsina of Angwusnasomtaqa by Brian Honyouti

If we’re talking about favorite landscapes, one of my favorite mountains resides in Four Corners. At 9977 feet, Sleeping Ute Mountain fills the horizon as one travels from Bluff to Cortez or Shiprock. In the southwestern corner of Colorado, the mountain is part of Montezuma County. Standing to the south, 8959 foot Hermano Peak forms the raised knees and the head at the north end is called Ute Peak.

The Utes believe this mountain range is a deity who will rise again if needed to fight his peoples’ enemies, a legend not unlike that of King Arthur. Sleeping Ute Mountain also figures in various Navajo rituals, including the Moving Upward Way and the Flint Way. Clouds form lovely atmospheric effects around this range and its peaks. I once thought I saw a small line of fluffy white rabbits hopping near its knees…

Growing up, I discovered my mother knew a great deal about antiques and craft work. When we went to live briefly in New Mexico in the early 1960s in Albuquerque (while my father went to grad school at UNM), I’d accompany my mother to Old Town. There, she developed a passion for what she claimed were Zuni owls, and bought two ceramic ones, each about seven or eight inches high. They were brightly painted: one in a pastel yellow and the other in a sky blue. Their faces had wide eyes and cleverly rendered beaks, and curved brush marks denoted feathers on their swelling chests.

Years later, after futilely searching the Southwest for brightly painted ceramic owls, I now realize that her acquisitions were actually Mexican tourist wares. But I bought this fine fellow in the pueblo a few years ago to remind me what a Zuni owl really looks like.

The history of American Indian arts is marked by Native reaction to and acceptance of judging, particularly by non-Natives. In the Southwest, this started as early as the 1920s, when the Santa Fe Indian Market and Gallup Inter-tribal Indian Ceremonial were established. In Santa Fe, the first judges were anthropologists and non-Native Indian arts patrons. In Gallup, non-Native Indian traders were the judges. Many Natives, especially those from the Pueblos, were embarrassed and discomfited by judging events. Competitive activities like prize awards didn’t always sit well with Indian neighbors; others, however, claimed that getting awards helped their careers.

Occasionally, the best attempts backfired. A friend of ours, a man in his sixties, speaks of a time when he discovered evidence that one particular award event had been “rigged.” He carried on, didn’t complain, and later when his career was solidly established, he pulled out of that competition for good.

Driving the highways and back roads of Indian Country means running into those yellow “Watch for Elk” signs from time to time. I’ll never forget coming face to face with a herd in the Grand Canyon’s South Rim. We were walking from the El Tovar Hotel over to the post office complex when we spotted a group of five adults and two youngsters. We were on a level park path and they were grazing about fifteen feet or so from where we were passing.

First of all, they were BIG! These guys, each adorned with a huge rack of glittering antlers, stood about eight or nine feet high. We could feel their sudden anxiety like a wave; we knew at once not to do anything other than move on quickly and quietly. No clicking of cameras, no matter how picturesque the view. No cooing or waving, or attempts to draw closer. It was a pity, for they are beautiful creatures—but they are wild animals and this was their turf.

When I saw this beaded fellow at Turquoise Village in Zuni last year, I knew he’d be the perfect commemorative souvenir.

I still believe that the renewed appreciation of Indian Country owes a great deal to the 1970s. When Native individuals began to receive media attention during that decade, it did much to aid a new look at Indian Country and its arts. A young and handsome Ray Tracey brought new luster to the Santa Fe Indian Market. In time, his jewelry would come to define Native American design, as it straddled a line between traditional form and contemporary sleekness. In Taos, R.C. Gorman’s dreamy prints featured an idealized and colorful Southwestern landscape, often peopled by enigmatic Native women in romantic clothing.

It was left to a non-Native, however, to introduce two fictional Navajo cops uncovering disturbingly familiar crimes on the vast reservation. Santa Fe journalist Tony Hillerman created young Jim Chee and more experienced Joe Leaphorn; these characters drew many of us into a best-selling mystery series.

Looking over the winning entries for the juried competition award list for the 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market, I see some titles that inspire chuckles and giggles. I’ve always enjoyed the sly nature of Indian humor, from Fritz Scholder to Diego Romero. A people who have decried their stereotyping often prove resilient in gaining revenge. Some of the winners of this year’s competition have had no compunction about mocking our contemporary society and its obsessions:

- Best of Class for Classification IV Wooden Carvings was “Techno Kid on the Run” by Stetson Hunyumptewa. A Hopi koshare pursues a naughty boy who is preoccupied with his smart phone and apps.

- In the non-traditional Baskets Classification, Pauline Tsosie produced a delight entitled “Paradigm Shift.”

- Two winners in the Mixed Media Classification were titled “Vexations” and “Power Struggle,” reminders that the days of “Bambi School of Art” prettiness are resoundingly rejected.

Will it be true that our 21st century is known as “The Age of Cynicism” by Natives and non-Natives alike?

I’ve watched this fair since I started attending in the early 2000s. I’d grown a little tired of the Santa Fe Indian Market and a chain of personal challenges made the direct flight from NY’s JFK to Phoenix’s Sky Harbor Airport a more viable choice. Initially, the Guild Fair had a tone of merriment not unlike a large crafts fair. A closer look, however, indicated that the goods on offer were much more than clever craft work. The grounds of the Heard Museum make for a good-natured, self-contained environment. The most notable thing I saw at once was that this show can be a more productive learning experience for the beginning collector. The SWAIA Indian Market is still the place for razzle-dazzle entries, high prices, and reputation-enhancing work. Yet, the arts that are displayed at the Heard show are often things that one call fall in love with quite easily. This year’s Guild Fair opens Saturday, March 3 and runs through Sunday.