What traveler to New Mexico ever fails to wonder at the state’s matchless clouds? In a recent visit we discovered it was easier to park along Old Town’s plaza and narrow streets than previously. Later on we heard that this part of the city has attracted gangs and petty crime. It made me glad we decided to park in the thick of things instead of the back parking lots.

One of the most venerable of Old Town’s attractions is the Covered Wagon, which has been selling Southwestern souvenirs since the 1940s. Its Indian arts are Route 66 curio goods, but the store remains fun and good-natured. If you have time for only one place in Old Town, check this store out. The best Indian arts on offer in Old Town are pottery and there are at least four fine shops to serve collectors and enthusiasts.

This year we finally ventured into Old Town Antiques, an interesting little shop with some good vintage jewelry. We also discovered through a friend a previously well-hidden treat, the restaurant Seasons. To better understand Old Town’s enduring appeal, check out the city’s history exhibits at the nearby Albuquerque Museum.

August clouds over Old Town Albuquerque, and the Covered Wagon.

August clouds over Old Town Albuquerque, and the Covered Wagon.

Main Street Albuquerque possesses various faces. The Nob Hill section not far from the University campus has become known for its antique stores and funky boutiques. One of the best destinations for those who love older Indian arts and souvenirs is Cowboys and Indians Antiques. This store is a collective of dealers who show older works within the building; the store also puts on one of the best antiques shows in the region — the Great Southwestern Antique Show. This show is usually held on the first weekend in August. Many collectors come out to New Mexico and start their investigations here before moving on to the antiques shows in Santa Fe held before the SWAIA Indian Market. I particularly like the two “sides” of this building: the unassuming west side with its large sign and the lively mural on the east side which shows that even graffiti can have a Southwestern flavor!

Cowboys and Indians Antiques, on Central Avenue, Albuquerque

Cowboys and Indians Antiques, on Central Avenue, Albuquerque

The other side of the building

The other side of the building

Like the Covered Wagon in Old Town, Skip Maisel’s store in downtown is one of the most famous curio shops along Route 66. Indian-made jewelry from Maisel’s shop, even though much was bench-produced, serves as popular vintage collectibles. The store is still going strong today and acts as many tourists’ introduction to souvenir Indian arts. Works by notable jewelers figure in the front cases, but the real goods—lots and lots of them—are the mass-produced necklaces, bracelets, pendants, and rings that line the aisles.

As always, what’s unfortunate is that these goods can be perceived as representing what genuine Indian-made arts are like. The fact is that curio jewelry usually is stuck in a mid-20th century stylistic time warp, reflecting designs that are called “traditional” and “classic.” In my forthcoming book, Southwestern Indian Bracelets: The Essential Cuff, I’ll be examining what really lies behind these labels and why they denote value judgments both good and bad.

Maisel’s Indian Jewelry & Crafts store, Albuquerque

Maisel’s Indian Jewelry & Crafts store, Albuquerque

Albuquerque is in Indian Country and the evolution of Pueblo Deco is one of the region’s more enjoyable architectural feats. There is an interesting connection between Indian arts and the Art Deco era. Although Art Deco began in France, its character changed when translated to a different country. In the United States, Art Deco is a proud mode for New York’s skyscrapers and other eastern public works and apartment buildings. When the style came to the Southwest, its creators saw an immediate affinity with indigenous architecture and building details.

The KiMo Theater on Central Avenue is one of the best examples of Pueblo Deco, and echoes can be found in other buildings up and down Central. Art Deco was an excellent style for appropriating folk and local imagery, using cheerful colors, and providing just the right amount of razzle-dazzle to perk up any neighborhood. Its exotic modernity makes downtown Albuquerque even more intriguing.

Detail of Pueblo Deco ornament on the KiMo Theater

Detail of Pueblo Deco ornament on the KiMo Theater

The KiMo Theater in downtown Albuquerque, NM

The KiMo Theater in downtown Albuquerque, NM

One of the most serious issues confronting the American Southwest is the maintenance of its water resources. The idea for those green golf links seen in Phoenix and Tucson comes from far away, and the water system is already overloaded on many levels. Drought and wildfires made this summer as hot and dry as ever. The Native peoples of the region value their water supplies and attempted to conserve as much as possible. Their dry farming, whether Pima or Hopi, reflects reasoned use of the land. No wonder, then, that water symbols play a great role in local Native design.

Tourists, too, require water when traveling through Indian Country. The best advice I can give those heading to the Southwest — even in the fall — is to stay hydrated. Drink lots of water, all the time, whether you’re following a trail or weaving your wall through a city mall.

Rain arrives in monsoon season. From Museum Hill near Santa Fe, NM

Rain arrives in monsoon season. From Museum Hill near Santa Fe, NM

Even though water is a rare commodity in the Southwest, hotels, golf courses, and municipal centers use water for fountains and golf courses.

Even though water is a rare commodity in the Southwest, hotels, golf courses, and municipal centers use water for fountains and golf courses.

Over the years I’ve been collecting Indian arts, I’ve occasionally run into individuals who express fascination with Native-made medicine bundles. Most of the time this interest stems from the New Age-shamanistic appreciation of American Indians; it’s a forlorn hope not to expect some of this starry-eyed attitude on the part of non-Indians. It’s certainly true that many spiritual beliefs from Native culture are beautiful, and attractive to pursue.

But I always cringe when I learn that some people believe medicine bundles made for Native individuals are yet another category of collectible. Genuine medicine bundles are made for a specific person, blessed, and have efficacy only for the person who carries them. This “power” is not transferable to any other persons, Native or otherwise. The materials that go into medicine bundles of earlier decades can include remarkable fetish-like carvings. Nevertheless, the collecting of medicine bundles isn’t appropriate. There are those who tell me and others, in quiet tones, that such an acquisition can bring ill luck to the collector.

Another major point to consider: almost all the medicine bundles available on the market are bogus. Don’t go there.

Gallup evening clouds

Gallup evening clouds

In the first year I started collecting, I consulted a Navajo gallery dealer about an overriding concern: I was not a collector with a lot of money. She understood my dilemma and questioned me about my passion for Southwestern Indian jewelry. After some discussion, she suggested I collect Indian rings. These items were not as expensive as other jewelry and could be picked up for reasonable prices. She also encouraged me to buy rings from young makers who might, in time, become notable artists.

As I studied the history of Indian design, I realized a significant change had occurred in the 1960s. Young Native artists had a chance to study together at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. They also took in other museums, and absorbed mainstream art history as part of their learning experience. I found this ring at Brimfield Market in Massachusetts in the early 1990s; the dealer assured me it was Indian-made. I’m sure he was correct, and I knew (after working there for five years in the 1980s) the very painting gallery room at the Museum of Modern Art where the ring’s maker drew his or her inspiration.

I have a real fondness for this city I once lived in as a child. I’m usually wary of urban progress for it so often creates visual urban blight. But over the last ten years, the city’s managers have resolved the difficult split and swell of traffic where I-40 and I-25 meet and cross. I still remember making the slow trip through Rio Rancho and Corrales just to avoid that transfer onto I-25 north to Santa Fe. This view out of our hotel window shows how small our petty human concerns are when matched against those ageless volcano guardians to the west of the city.

The Big I, where I-25 and I-40 meet.

The Big I, where I-25 and I-40 meet.

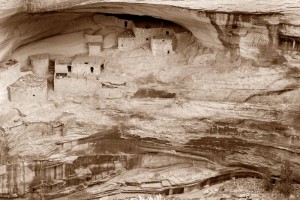

We’ve only been there once, but we will never forget Three Turkey Ruin, situated off the Canyon de Chelley perimeter road. The remnants of a nineteen room Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwelling can be accessed on a dirt road. If you peruse the Indian Country road map, this dirt road veers east and also provides a short cut to Fort Defiance; this drive is more direct than going around the main paved roads to Ganado and then east to Window Rock.

We made the mistake of taking this dirt road one late autumn afternoon, already dwindling into dusk. Recent rain and snow had created a soupy coating of mud on the road that threatened to bog down our four wheel drive. As night fell, the lack of lights around us and the fact that we were going through tree-filled wilderness, fueled our unease. Small paths split off to habitations we couldn’t see, the mud sucked at our wheels like quicksand and our hearts thudded with growing panic. Our car would bog down miles from anywhere and no one else would be traversing this road. My husband floored the vehicle, afraid to brake, and we kept going on a road that seemed to climb at an elevation. Just when we felt the first pangs of real terror, the road hit pavement. We’d made Fort Defiance.

I remember us eating a celebratory taco dinner at the Navajo Nation Motor Inn. I suspect others have an adventure like this to report. It taught us one thing, for sure. Never travel a road because it seems like a good shortcut!

Three Turkey Ruin (from dawnKIS photography: http://bit.ly/T4EtPt)

Three Turkey Ruin (from dawnKIS photography: http://bit.ly/T4EtPt)

I’m not an urban planner by trade, but sometimes caring about something causes ideas to form. Border towns do have their dark sides, with plentiful bars to cater to those whose thirst for liquor exceeds their good sense. As a collector of American Indian jewelry, I’m also aware that Gallup can cater to the darker side of the Indian jewelry business with its back room silversmiths turning out specious works. Yet there’s truth in the title “Indian Jewelry Capital of America.” Much jewelry does pass through here.

There is so much on offer here in terms of local businesses, restaurants, shops, and the remaining Indian arts shops of merit. I see the local WalMart as an example of the successful integration of local Native, Hispanic, and Anglo cultures. There are beautiful murals throughout the city, a nice local history museum in the train station, and attractive architecture. Gallup’s residents need to rework its reputation as a Gateway to Indian Country, with an emphasis on the positive. Gallup is a workaday place, but it draws great local loyalty. At the Gallup hotel we stayed in recently, the young desk clerk, who looked Indian, told us with pride that she loved where she lived.

America always seems to require help in understanding its Native peoples, and our outmoded social studies curricula for schools doesn’t help matter by placing Indians firmly in the past. Native culture is alive and well in Gallup as the Saturday parade demonstrated. Yet, just as trading posts have changed in the face of modernism, so must the story alter to fit the times.

Even a parking lot in Gallup is an opportunity to celebrate art and culture, in this case Mibres images.

Even a parking lot in Gallup is an opportunity to celebrate art and culture, in this case Mibres images.