For years we traveled along the interstate to and from Albuquerque, stopping off at the ratty Dairy Queen located at Rio Puerco. The rest stop is the first real one you reach either just before cresting the hills to see Albuquerque sprawled ahead or after leaving the city and its towering peaks behind. This summer we came from the west and discovered a gleaming casino in what was once a care-worn relic of Route 66. (The appropriately named Route 66 Casino Hotel is operated by Laguna Pueblo.) But the Dairy Queen is still there, surrounded by shiny chrome walls and all the elements of a first-rate truck stop. The tacky souvenirs were intact, too — just better housed. Ah, progress!

(Historic note: On the other side of I-40, on old Route 66, is the historic Rio Puerco Bidge, maintained by the National Park Service.)

The new Dairy Queen at Rio Puerco, along Route I-40, part of the Route 66 Casino. Photo © 2012 by Barry Katzen

The new Dairy Queen at Rio Puerco, along Route I-40, part of the Route 66 Casino. Photo © 2012 by Barry Katzen

With nearly thirty years of Indian Country travel behind us, one place always brings a smile. If we decide to travel to Teec Nos Pos, a trading post in Apache County, Arizona, we know our experience will be a good one. The original trading post was started in 1905, but the one we go to nowadays was rebuilt near the intersection of US Highways 160 and 64 after a fire in 1959. The name translates to “Cottonwoods in a Circle.” The trading post does utilitarian duty as a supplier for local Navajo families. Its rug room on the far right side has brought us rewards over the years. The Teec Nos Pos style of Navajo weaving is almost “Oriental” in its intricate designs; we have, however, also found fine pictorial weavings here, including my “Merry Christmas” piece.

Teec Nos Pos Trading Post

Teec Nos Pos Trading Post

One time after a bad case of salmonella rendered me incapable of making Mesa Verde’s holiday celebration, we drove to Teec in search of a restorative. An hour in the rug room banished all aches and pains. XE3G7GEHUBES

The entrance to the trading post’s Rug Room.

The entrance to the trading post’s Rug Room.

The other day I got a book out of the library at the college where I work. Catherine C. Robbins wrote All Indians Do Not Live in Teepees (or Casinos) (University of Nebraska Press, 2011) based on many years of journalistic pursuits in the Southwest. Her stories from Indian Country cover a wide range of topics and issues. One of my favorite chapters, however, concerns the Indian artist’s frustration with the “buckskin ceiling” applied to Native art-making. Sometimes this ceiling is also a box: one in which non-Native expectations of how Indian art should look remain “pickled” in the past. Native artists have been rolling their eyes about this problem since the 1960s.

When I write about Indian jewelry, I work hard to make it clear that labels used for certain jewelry forms have come from outsiders. What is traditional seems silly when one looks at Southwestern Indian metal jewelry-making. Unlike in Mesoamerica, Natives of the American Southwest did not acquire the process of metallurgy until its colonial era when Mexican and then European American settlers (many of them soldiers) taught them the craft.

We are among those individuals who vastly prefer Gallup to Santa Fe. At this point, some of you will wish to roll your eyes and stop listening. I remember Santa Fe from the early 1960s. Yes, I was a young girl then, but Santa Fe truly had the look and feeling of a small European city to someone from upstate New York. In the intervening decades, Santa Fe’s charm has been whittled away by the demands of tourism and urban planning. With Gallup, what you see is what you get.

Gallup is a railroad town and its tracks define the whole sinuous curve of its old Route 66 highway. The rest of the town is sprawled over its rolling hills and graceful valleys. Because it serves as a reservation border town, Gallup has also attracted the least admirable publicity. Back east, I know people who shiver at the mention it, speaking in shocked tones of horrible car accidents, drunks staggering along streets, and an unnamed discomfort. Friends of ours from Arizona shake their heads at our affection for it, claiming they’d only stop in Gallup for a gas station.

When we visit Gallup, we get a sense of what the West is really all about. We don’t need a movie set, a romantic view of mesas and buttes, or a string of trendy eateries to feel that here is a place where real people live, work, visit, shop, and that life in a railroad town is about staying put while all about one is motion. The people are nice, too, friendly in a way that is far more realistic than people one encounters in a popular tourist destination.

A train arrives in Gallup — one of many arrivals every day.

A train arrives in Gallup — one of many arrivals every day.

The 2008-9 Great Recession threw many non-profit cultural institutions into a tailspin; funding curtailments brought big changes to operations that had always maintained some measure of continuity. Almost overnight, these organizations discovered that they needed to apply business solutions; some places succeeded in making transitions, while others ended up damaging aspects of their original mission. The Gallup Ceremonial’s problems don’t stem simply from a lack of cash. The event needs to reevaluate the state of Indian arts today, what requirements drive local tourism, and how aiding the local community can be balanced with bringing in more visitors who want to see and participate in something unique and special.

What worked well from the 1920s up to the last quarter of the twentieth century no longer meets the demands of the 21st century. That doesn’t mean throwing out the baby with the bath water, however. The Ceremonial’s directors and sponsors need a new vision of just what can refresh its traditions while creating an added impetus for attending. What exactly brings locals and visitors together? In the past, those who respected Indian culture (like me) enjoyed coming to partake of things that wouldn’t ordinarily be available when just passing through as a tourist.

One idea I hear from those who live in or near Gallup is that the Ceremonial needs to be brought back to downtown Gallup. The SWAIA Indian Market benefits greatly from being held on Santa Fe’s Plaza and adjoining streets. The aura of street festival is hard to beat, and Red Rock Park’s buildings look very tired and in need of structural reinforcement. A place to begin is with the bathrooms: the facilities in Gallup’s busy WalMart look much better than those at the park…

At the entrance to the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial

At the entrance to the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial

Nevertheless, the Ceremonial isn’t dead yet, not by a long road. There are those still loyal to its original premise when founded in the 1920s, that this would be an important venue for Indian arts at their best. What many people forget, also, is that this is an event for bringing Native peoples together. I might prefer a powwow to a rodeo, but there’s entertainment for the locals and the venue can be a source of pride—a destination. I certainly saw this on Saturday morning when we pulled onto I-40 and glimpsed the large, healthy crowd downtown for the parade.

Back in the 1930s, the Indian traders held sway. Newspaper articles in following decades largely gave Native artists short shrift and reported on which trader booth had received the most awards for arts. Patronage has changed, and the list of corporate sponsors is a telling statement about what businesses today can afford to be sponsors. The Arts judges are also leading figures in the field. Later that week,in Santa Fe, I spoke with one judge who expressed some concern about the changing of categories for prizes. This created difficulties for some artists. For example, I saw fewer entries from Zunis than expected. It may be that the Ceremonials sponsors need to clarify and establish less flexible guidelines and attempt a wider range of fundraising.

My summer in the Southwest yielded other stories about institutions reorganizing, sometimes in rather alarming fashion. I discovered in Santa Fe that the Indian Arts and Crafts Association (IACA) had recently eliminated its paid staff for an all-volunteer staff.

At the entrance to the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial in Red Rock Park

At the entrance to the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial in Red Rock Park

This question has often come up over the years. This year, we were in a position to attend and pulled into the parking lot for the Friday August 9 day of the annual event. There were a lot fewer cars than we remembered. An immediate disappointment arose when we bought our tickets and learned that the powwow had been canceled. The booths along the perimeter of the buildings had Natives selling stuff that was definitely NOT locally made. Inside, things seemed back to normal except for the fact that the interior booths were reduced to a very small number. I remember when the booths lined the entire perimeter of the great hall.

Can we blame the recession? Yes, but there seems to be a more complex string of issues. Those who run and organize the Ceremonial have been plagued by fundraising woes. I recall about five years ago they turned to the state for funding solutions. Ooops! One reality is that the number of active trading posts with powerful followings of artists and collectors has greatly diminished. Trading posts are not what they once were, and Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado AZ may soon be one of the few real remaining relics of this enterprise.

The outdoor booths at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial.

The outdoor booths at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial.

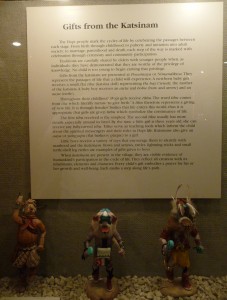

While staying at a Scottsdale resort in early August, I discovered it had a Native American Cultural Discovery exhibit. I’m always interested in finding out what those in the hotel business consider important for visitors to learn about Indians. The decent-sized room had several cases that focused on kachinas, or katsinum as they’re called by the Hopi. These Pueblo Indians are not the only ones to have developed a large hegemony of sacred beings, but their carved cottonwood dolls are one of the greatest categories of collectibles in the American Southwest.

Hopi katsinem are also one of the most recognizable “brands” of types of Indian arts. They vary from elaborate sculptures worth thousands of dollars to modest handmade figures sold at souvenir prices. I find the katsina figure to be a real paradox: on one hand, it represents a genuine sacred spirit possessed of powers important to the Hopis and a means of teaching their children, on the other hand it conveys an immediate exoticism and “otherness” that specific souvenirs conjure up just by their existence.

Gifts from the Katsinem

Gifts from the Katsinem

Katsina of Angwusnasomtaqa by Brian Honyouti

Katsina of Angwusnasomtaqa by Brian Honyouti

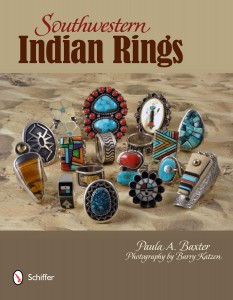

Join us for a book signing of Southwestern Indian Rings!

When: Thursday, August 16, 5 pm.

Where: Collected Works Bookstore, 202 Galisteo Street, Santa Fe.

We’d love to see you there!

If we’re talking about favorite landscapes, one of my favorite mountains resides in Four Corners. At 9977 feet, Sleeping Ute Mountain fills the horizon as one travels from Bluff to Cortez or Shiprock. In the southwestern corner of Colorado, the mountain is part of Montezuma County. Standing to the south, 8959 foot Hermano Peak forms the raised knees and the head at the north end is called Ute Peak.

The Utes believe this mountain range is a deity who will rise again if needed to fight his peoples’ enemies, a legend not unlike that of King Arthur. Sleeping Ute Mountain also figures in various Navajo rituals, including the Moving Upward Way and the Flint Way. Clouds form lovely atmospheric effects around this range and its peaks. I once thought I saw a small line of fluffy white rabbits hopping near its knees…