Growing up, I discovered my mother knew a great deal about antiques and craft work. When we went to live briefly in New Mexico in the early 1960s in Albuquerque (while my father went to grad school at UNM), I’d accompany my mother to Old Town. There, she developed a passion for what she claimed were Zuni owls, and bought two ceramic ones, each about seven or eight inches high. They were brightly painted: one in a pastel yellow and the other in a sky blue. Their faces had wide eyes and cleverly rendered beaks, and curved brush marks denoted feathers on their swelling chests.

Years later, after futilely searching the Southwest for brightly painted ceramic owls, I now realize that her acquisitions were actually Mexican tourist wares. But I bought this fine fellow in the pueblo a few years ago to remind me what a Zuni owl really looks like.

Recent travel articles in The New York Times and some magazines invariably depict some view of Monument Valley when extolling the glories of the Navajo reservation. Covering nearly 100 square miles, the area’s 30,000 acres became a Navajo Tribal Park in 1958. Before that, in the 1930s and 40s, John Ford made the place famous in his Hollywood movies. In fact, if we called Monument Valley iconic, we wouldn’t be wrong.As landscapes go, this one is rightly associated with Indian Country in people’s minds.

Its sheer scope, along with isolated mesas and buttes, was sculpted in the Cenozoic era when the region was under water. When the sea receded, what remained left behind were beds of sand. These hardened and compacted into the hundreds of stone formations so beloved of photographers.

Countless writers and journalists speak of the magic of the region, and how visiting this area clears their heads from every day cares and distractions. One personal note: after brain surgery in early 2002, I decided I wanted to go to Monument Valley for just those reasons later that year. What I had forgotten, however, is that it sits 4800 to 5700 feet above sea level. I had a wonderful time, except for the headaches!

With the national presidential campaign about ready to have its two candidates go face to face, one wonders what recognition Obama and Romney will make of their Native voters? Indians didn’t get the vote in America until 1924, four years after women received that right. Romney was governor of a state that swept most of its tribes away. As a Mormon, his fellows in faith have had mixed relations with Native peoples. President Obama’s profile about Native concerns is equally questionable. This year, the media has expressed interest in the voting of the Four Corners states in swaying the election. These votes include those from Indian Country. Many Natives in this region vote Democratic but come from conservative backgrounds.

The history of American Indian arts is marked by Native reaction to and acceptance of judging, particularly by non-Natives. In the Southwest, this started as early as the 1920s, when the Santa Fe Indian Market and Gallup Inter-tribal Indian Ceremonial were established. In Santa Fe, the first judges were anthropologists and non-Native Indian arts patrons. In Gallup, non-Native Indian traders were the judges. Many Natives, especially those from the Pueblos, were embarrassed and discomfited by judging events. Competitive activities like prize awards didn’t always sit well with Indian neighbors; others, however, claimed that getting awards helped their careers.

Occasionally, the best attempts backfired. A friend of ours, a man in his sixties, speaks of a time when he discovered evidence that one particular award event had been “rigged.” He carried on, didn’t complain, and later when his career was solidly established, he pulled out of that competition for good.

Driving the highways and back roads of Indian Country means running into those yellow “Watch for Elk” signs from time to time. I’ll never forget coming face to face with a herd in the Grand Canyon’s South Rim. We were walking from the El Tovar Hotel over to the post office complex when we spotted a group of five adults and two youngsters. We were on a level park path and they were grazing about fifteen feet or so from where we were passing.

First of all, they were BIG! These guys, each adorned with a huge rack of glittering antlers, stood about eight or nine feet high. We could feel their sudden anxiety like a wave; we knew at once not to do anything other than move on quickly and quietly. No clicking of cameras, no matter how picturesque the view. No cooing or waving, or attempts to draw closer. It was a pity, for they are beautiful creatures—but they are wild animals and this was their turf.

When I saw this beaded fellow at Turquoise Village in Zuni last year, I knew he’d be the perfect commemorative souvenir.

I still believe that the renewed appreciation of Indian Country owes a great deal to the 1970s. When Native individuals began to receive media attention during that decade, it did much to aid a new look at Indian Country and its arts. A young and handsome Ray Tracey brought new luster to the Santa Fe Indian Market. In time, his jewelry would come to define Native American design, as it straddled a line between traditional form and contemporary sleekness. In Taos, R.C. Gorman’s dreamy prints featured an idealized and colorful Southwestern landscape, often peopled by enigmatic Native women in romantic clothing.

It was left to a non-Native, however, to introduce two fictional Navajo cops uncovering disturbingly familiar crimes on the vast reservation. Santa Fe journalist Tony Hillerman created young Jim Chee and more experienced Joe Leaphorn; these characters drew many of us into a best-selling mystery series.

Bruce Bernstein, the Director of SWAIA, has had a long and distinguished career in the world of Indian arts. His scholarship is top-notch. I recently reread a piece by him in an anthology, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century: Makers, Meanings, Histories. In doing research for my next book on Southwestern Indian bracelets, I found an article he’d contributed to the anthology on how the 1960s and 1970s provided new contexts for Indian arts. Bernstein pointed out the start of an international profile for Indian artists, including foreign exhibitions for selected individuals. He describes how changes in the American social and intellectual climate helped make Native American Studies an academic discipline.

My own education in the first half of the 1970s occurred too early to benefit from this. My dual major of art history and anthropology of the North American Indian (a mouthful) shows how great the emphasis on anthropology still was at that time. The creation of Native American Studies helped usher in a multidisciplinary — and interdisciplinary — approach to Native art production. Bernstein also wisely points out that the “traditional” arts with their handcrafted nature made them popular in America in general. Even their introduction into home decoration played a role we still recognize today.

One of the most interesting facts brought out at the “Geronimo” exhibition at the Heard Museum concerns his life after raiding, running, and imprisonment. The canny man recognized his notoriety was capable of making him money. He sold the buttons from his clothes to souvenir hounds, and found other outlets for his new-found marketing and self-promotion skills. I see this aspect of his life as ironic and perhaps inevitable. Along with Pocahontas, Geronimo may rank as the best-known of all historical American Indians.Even Edward Curtis’s portrait of Geronimo in old age captures the iconic nature of the man—who knew he was an icon and just how much this could net him.

The U.S. government’s covert campaign to capture and take down Osama Bin Laden was code-named “Operation Geronimo.” This gesture was a belated token of respect for a Native man who kept the U.S. Army on the run for many years.

“Beyond Geronimo: The Apache Experience” runs through January 20, 2013.

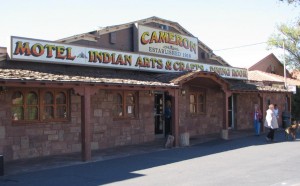

One of our favorite rides is from Cameron to the eastern entrance of the Grand Canyon at Desert View. The Cameron Trading Post has come to symbolize the best and worst of Southwestern souvenirs. The town and trading post are named after Ralph H. Cameron, a noted entrepreneur of the Grand Canyon’s attractions and one of the last territorial delegates from Arizona to the U.S. Congress. Cameron also became a U.S. senator from Arizona, which is enjoying its one-hundredth anniversary of statehood this year.

This portion of Highway 64 was originally made by the Fred Harvey Company so its famous “Indian Detours” could convey tourists to the Canyon’s South Rim. This great stretch of road climbs and drops 3000 feet in 35 miles.