The city’s Central Avenue is its Main Street—and it’s also the original Route 66. When moving out to New Mexico in 1962, my parents and I arrived on Central Avenue after coming west from the start of Route 66. We’d just driven in to the city in our big Oldsmobile, when we were suddenly rear-ended! The lady behind us had been staring into a hat (!) shop and forgot to brake in time. The car was so big and sturdy in its metallic body that I wasn’t hurt at all, just thrown onto the floor of the wide back seat.

The Route 66 craze brought a lot of tourists to the state and Central Avenue catered to their needs with restaurants, gift shops, and a slew of adobe motels with swimming pools. I remember those years hazily, but do recall that fast cars, food, and music were entering into our popular culture. I even remember several drive-ins, watching World War II and science fiction movies from the backseat while the dark outline of the Sandias hovered in the background.

Downtown Albuquerque, on Central Avenue.

Downtown Albuquerque, on Central Avenue.

Great independent bookstores have a pulse all their own. Collected Works in downtown Santa Fe stocks works which spell out the various charms of the Southwest. Their sections on local history, area maps, and Native cultures surpass even the museum bookshops. Yet other areas, such as cookery and small business are also on target. One gets a sense of the cultural diversity of the region, but not at the expense of other critical subjects. Collected Works blooms during events like the SWAIA Indian Market, where they gather new and experienced authors for reading and signings. Santa Fe shopping has changed over the years, but one of the greatest finds for the Indian Country visitor could be that short-run guide to the Turquoise Trail or a novel about a struggling Native weaver who learns from Hispanic artists in the Chama area.

Collected Works Bookstore and Coffeehouse, in Santa Fe.

Collected Works Bookstore and Coffeehouse, in Santa Fe.

It happened about a year ago to us. It’s one of the inevitable reactions for the tourist in Indian Country, although it doesn’t occur that frequently. We’d risen early to get on I-40 and head eastbound, windshield visor up to deflect the rising sun. It was only about 7 or 7:30 a.m. when we pulled into the McDonald’s off one of the exits in Holbrooke. We ran to the bathroom at once before buying anything. An Indian woman employee was sweeping the still damp floor and the sight of me seemingly disgusted her. She glared at me as I bypassed the “wet floor” stanchion. When I emerged to wash my hands, she observed me pointedly, muttering under her breath.

This past month we revisited the same restaurant at a slighter later hour. No one was cleaning the restrooms and the staff at the counter possessed a weary good nature. Why even write about this? Because such encounters can pierce the bubble we tourists often travel in: that everyone is glad to cheer us on our way. Most Natives I talk to in Indian Country are happy to have work when they get it, but on-the-job discontent knows no ethnic boundaries…

Main Street Albuquerque possesses various faces. The Nob Hill section not far from the University campus has become known for its antique stores and funky boutiques. One of the best destinations for those who love older Indian arts and souvenirs is Cowboys and Indians Antiques. This store is a collective of dealers who show older works within the building; the store also puts on one of the best antiques shows in the region — the Great Southwestern Antique Show. This show is usually held on the first weekend in August. Many collectors come out to New Mexico and start their investigations here before moving on to the antiques shows in Santa Fe held before the SWAIA Indian Market. I particularly like the two “sides” of this building: the unassuming west side with its large sign and the lively mural on the east side which shows that even graffiti can have a Southwestern flavor!

Cowboys and Indians Antiques, on Central Avenue, Albuquerque

Cowboys and Indians Antiques, on Central Avenue, Albuquerque

The other side of the building

The other side of the building

Like the Covered Wagon in Old Town, Skip Maisel’s store in downtown is one of the most famous curio shops along Route 66. Indian-made jewelry from Maisel’s shop, even though much was bench-produced, serves as popular vintage collectibles. The store is still going strong today and acts as many tourists’ introduction to souvenir Indian arts. Works by notable jewelers figure in the front cases, but the real goods—lots and lots of them—are the mass-produced necklaces, bracelets, pendants, and rings that line the aisles.

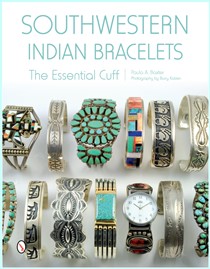

As always, what’s unfortunate is that these goods can be perceived as representing what genuine Indian-made arts are like. The fact is that curio jewelry usually is stuck in a mid-20th century stylistic time warp, reflecting designs that are called “traditional” and “classic.” In my forthcoming book, Southwestern Indian Bracelets: The Essential Cuff, I’ll be examining what really lies behind these labels and why they denote value judgments both good and bad.

Maisel’s Indian Jewelry & Crafts store, Albuquerque

Maisel’s Indian Jewelry & Crafts store, Albuquerque

One of the most serious issues confronting the American Southwest is the maintenance of its water resources. The idea for those green golf links seen in Phoenix and Tucson comes from far away, and the water system is already overloaded on many levels. Drought and wildfires made this summer as hot and dry as ever. The Native peoples of the region value their water supplies and attempted to conserve as much as possible. Their dry farming, whether Pima or Hopi, reflects reasoned use of the land. No wonder, then, that water symbols play a great role in local Native design.

Tourists, too, require water when traveling through Indian Country. The best advice I can give those heading to the Southwest — even in the fall — is to stay hydrated. Drink lots of water, all the time, whether you’re following a trail or weaving your wall through a city mall.

Rain arrives in monsoon season. From Museum Hill near Santa Fe, NM

Rain arrives in monsoon season. From Museum Hill near Santa Fe, NM

Even though water is a rare commodity in the Southwest, hotels, golf courses, and municipal centers use water for fountains and golf courses.

Even though water is a rare commodity in the Southwest, hotels, golf courses, and municipal centers use water for fountains and golf courses.

I have a real fondness for this city I once lived in as a child. I’m usually wary of urban progress for it so often creates visual urban blight. But over the last ten years, the city’s managers have resolved the difficult split and swell of traffic where I-40 and I-25 meet and cross. I still remember making the slow trip through Rio Rancho and Corrales just to avoid that transfer onto I-25 north to Santa Fe. This view out of our hotel window shows how small our petty human concerns are when matched against those ageless volcano guardians to the west of the city.

The Big I, where I-25 and I-40 meet.

The Big I, where I-25 and I-40 meet.

I’m not an urban planner by trade, but sometimes caring about something causes ideas to form. Border towns do have their dark sides, with plentiful bars to cater to those whose thirst for liquor exceeds their good sense. As a collector of American Indian jewelry, I’m also aware that Gallup can cater to the darker side of the Indian jewelry business with its back room silversmiths turning out specious works. Yet there’s truth in the title “Indian Jewelry Capital of America.” Much jewelry does pass through here.

There is so much on offer here in terms of local businesses, restaurants, shops, and the remaining Indian arts shops of merit. I see the local WalMart as an example of the successful integration of local Native, Hispanic, and Anglo cultures. There are beautiful murals throughout the city, a nice local history museum in the train station, and attractive architecture. Gallup’s residents need to rework its reputation as a Gateway to Indian Country, with an emphasis on the positive. Gallup is a workaday place, but it draws great local loyalty. At the Gallup hotel we stayed in recently, the young desk clerk, who looked Indian, told us with pride that she loved where she lived.

America always seems to require help in understanding its Native peoples, and our outmoded social studies curricula for schools doesn’t help matter by placing Indians firmly in the past. Native culture is alive and well in Gallup as the Saturday parade demonstrated. Yet, just as trading posts have changed in the face of modernism, so must the story alter to fit the times.

Even a parking lot in Gallup is an opportunity to celebrate art and culture, in this case Mibres images.

Even a parking lot in Gallup is an opportunity to celebrate art and culture, in this case Mibres images.

With nearly thirty years of Indian Country travel behind us, one place always brings a smile. If we decide to travel to Teec Nos Pos, a trading post in Apache County, Arizona, we know our experience will be a good one. The original trading post was started in 1905, but the one we go to nowadays was rebuilt near the intersection of US Highways 160 and 64 after a fire in 1959. The name translates to “Cottonwoods in a Circle.” The trading post does utilitarian duty as a supplier for local Navajo families. Its rug room on the far right side has brought us rewards over the years. The Teec Nos Pos style of Navajo weaving is almost “Oriental” in its intricate designs; we have, however, also found fine pictorial weavings here, including my “Merry Christmas” piece.

Teec Nos Pos Trading Post

Teec Nos Pos Trading Post

One time after a bad case of salmonella rendered me incapable of making Mesa Verde’s holiday celebration, we drove to Teec in search of a restorative. An hour in the rug room banished all aches and pains. XE3G7GEHUBES

The entrance to the trading post’s Rug Room.

The entrance to the trading post’s Rug Room.

The other day I got a book out of the library at the college where I work. Catherine C. Robbins wrote All Indians Do Not Live in Teepees (or Casinos) (University of Nebraska Press, 2011) based on many years of journalistic pursuits in the Southwest. Her stories from Indian Country cover a wide range of topics and issues. One of my favorite chapters, however, concerns the Indian artist’s frustration with the “buckskin ceiling” applied to Native art-making. Sometimes this ceiling is also a box: one in which non-Native expectations of how Indian art should look remain “pickled” in the past. Native artists have been rolling their eyes about this problem since the 1960s.

When I write about Indian jewelry, I work hard to make it clear that labels used for certain jewelry forms have come from outsiders. What is traditional seems silly when one looks at Southwestern Indian metal jewelry-making. Unlike in Mesoamerica, Natives of the American Southwest did not acquire the process of metallurgy until its colonial era when Mexican and then European American settlers (many of them soldiers) taught them the craft.