About six months ago, a rival colleague had told the director that word had gotten out of a discovery of a cache of Slender-Maker-of-Silver jewelry marked with the S-shaped hallmark. A former pot hunter turned respectable was quietly hawking these pieces, contacting selected individuals in the field. Tom Vaughn, now running a small non-profit cultural center near Albuquerque, had been contacted by the would-be former pot hunter; Tom, in turn, informed Matilda through a former colleague of hers, since Matilda’s museum had deeper pockets.

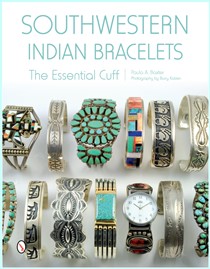

Antique American Indian jewelry with a spurious provenance had been the downfall of some professionals in the world of Southwestern Native America. According to Roy Climmer, Vaughn had seen some of the pieces briefly and he thought Matilda should try to acquire at least one, a handsome cluster bracelet. Vaughn was someone she trusted, and this had propelled her into action.

But to her disappointment, Matilda had flown to Albuquerque only to discover that Tom Vaughn was in Central America co-leading a fundraising tour. Sitting quietly in her booth, the warm New Mexico sunshine splashed across the table, she couldn’t help but feel anxious. She’d been surprised when Climmer first spoke to her about the man and the bracelet he possessed. At one time Matilda thought Roy had shown some romantic interest in her; she’d rebuffed him politely, still unsure about his feelings, but since then he’d never show any emotion toward her except fellowship.

A shadow fell across the sunny table top and Matilda looked up to see the waitress was cleaning the adjacent booth. She sent a sympathetic smile to her and Matilda instinctively smiled back.

“Waiting for someone special?” the woman asked.

“Yeah, you could say so,” Matilda said. “But he’s running late.”

“Oh, he’ll be here,” the waitress said hearteningly. “How could he pass up meeting someone so pretty?”

Her soft words sounded genuine and Matilda smiled again, pleased at the friendly reassurance. At the same time, she felt compelled to add, “But it’s a business meeting. This guy has something I want to buy.” Why had she even been this forthcoming? But there was something about the young woman, maybe the fact that she seemed to be around her age, which loosened her tongue.

Of course, it was the “Land of Enchantment” kicking in. Matilda knew her upbringing had been pretty much New England reserved; people in her family were not free with confidences or confessions.

“An artist? We’ve got plenty of those here, and I’m not talking about our vendors,” the young woman said fondly. “Some of our local talent fetch high prices in Santa Fe and Scottsdale.”

Matilda suddenly wished that such was her meeting, that she would soon greet an artist intent on explaining his or her vision. Now the doubts she’d been busily trying to bury started climbing to the surface. Maybe it wasn’t too late. She could get up, pretend she’d left something behind, and drive back to her motel.

A bustle near the entrance alerted both women to a newcomer. Matilda watched with bemusement as the sunny expression on the waitress’s face faded into one of distaste. She even gazed back at Matilda for a moment as if in reproach. Then she squared her shoulders and moved off to the kitchen.

The guy was tall, lanky. Matilda thought he carried a certain invisible authority with him. He was sunburnt, wore light stubble on his cheeks and chin, and had ash blonde hair that hung down to his shirt collar. He swiveled around, surveying the room, until he spotted her. Was that a predatory gleam in his eye, or was she just imagining things? He reminded her as nothing so much as a redneck good old boy — something that embarrassed her as soon as she thought it.

Perhaps it was the waitress’s disdainful attitude that reanimated her uncertainty. This man was precisely the sort of individual she’d been expecting to meet. For one brief second she had a vision of her finely groomed, fastidious director meeting this guy and she repressed a snort. He’d spotted her now and loped over to the table before folding his long limbs into the seat opposite her.

“Sure nice to meet ya, Miss Townshend,” he said, his watery blue eyes ogling her in a manner she’d rarely had to confront up close. “Old Roy said ya was a looker, and he was right.”

“Would you like something to eat?” she asked. His look took in her barely touched sandwich and he smirked, making her uncomfortably aware that he guessed her anxiety.

“Hey, Betty Lou!” he shouted over to the woman who’d waited on Matilda. She arrived smiling, and he ordered huevos rancheros with black coffee. She brought him a steaming cup and disappeared into the kitchen.

“I figgered you’d like to see the item in question,” he said, pulling a brown silver keeper pouch out of his thin windbreaker. He unlaced the strings and placed the pouch on the table in front of Matilda’s plate. She bent forward to stare; all she’d been told was that the bracelet was a cluster cuff, something that had especially intrigued her. This piece was not clusterwork: multiple stones set in small bezel holders. Instead, the thick curved band was clearly cast work. The silver was coin, a rich dark gray with a fine patina. Carefully, Matilda picked the pouch up and turned it in various angles. The composition of the bracelet band was dazzling; the piece looked like a starburst of finely curving lines launched from a central point. Along the ends of the band were finely chiseled grooves. The style was suitably ancient, from a period when stamps and dies were rare and handmade.

(Continued next week)